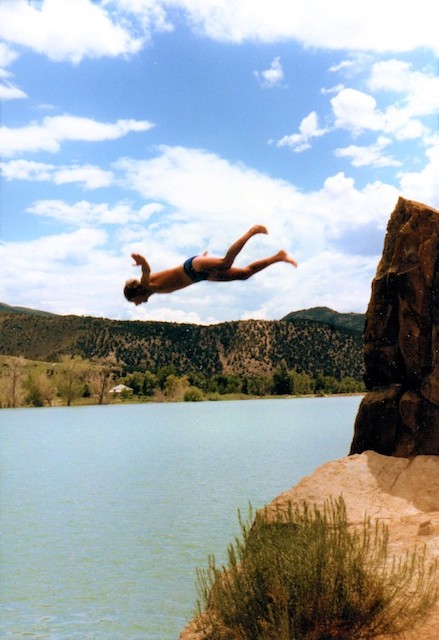

On a perfect summer afternoon in 1984, I climbed up a bluff to dive into a lake that geology students had been swimming in for decades. It was a tradition. I looked down to see what I was about to dive into and saw nothing to worry me, except the height.

Just before I took the plunge, my buddy Randy yelled “Don’t be an idiot. Let me see what’s in the water first”. The water was usually clear, but a recent rain had made it opaque with mud. Randy swam over to the base of the cliff where I was going to dive. He then stood up in water that’s usually about 20 feet deep. He was standing on a large tree submerged about 4 feet below the surface. Had I taken the leap, I would have paid a terrible price for my negligence. My fellow geology student had saved my life by simply looking before I took the leap.

I moved to a different part of the cliff and then flung myself off like a frog and safely splashed down.

Buying a mobile home park is a lot like diving into that lake: it seems like there is no risk. After all they are not like factories, gas stations or urban tracts. The environmental risk is not obvious.

By the time I was first asked to perform an environmental assessment on a mobile home park, I had been doing pre-purchase studies for about 25 years. I had assessed just about every type of property you could imagine and thought I had seen it all. I told the client that it was a waste of money and turned the work down. The client was smarter than me and called back in a few days and insisted. Twelve years and over 1,500 mobile home parks later, I have a very different opinion.

Risk = Probability x Consequences.

When you take a swim off the Atlantic Coast, the odds of meeting a shark are low. However due to the nature of the consequences, it is prudent to look first. The same is true of buying mobile home parks. The odds of finding an issue are not overwhelming, but the consequences can be dire.

So what are the environmental risks associated with mobile home parks?

You can generally divide the common risks into four categories:

1) Contaminated soil and/or groundwater on the property.

This can result from above/underground storage tanks, meth lab dump sites, dumping/spillage of waste fluids, burial of wastes and past industrial usage, including everything from gas stations and dry cleaners to landfills.

2) Off-site sources of soil and/or groundwater contamination.

Contamination moves underground and can migrate on to a park from an adjoining property. The park may look great, but nasties can find their way on to the property from nearby gas stations, petroleum bulk plants, agronomy plants, dry cleaners, landfills, metal plating shops and other industrial facilities. Stuff that leaks into the soil from other properties is often carried significant distances by groundwater, depending upon the geology. Additionally, contaminants in the form of vapors also move around through soils and cross property lines.

3) Operational Units

Functional parts of a park, such as water supply wells, wastewater treatment plants and home heating oil tanks involve risk in more than one way. When these types of units fail, they can pollute soil and/or groundwater. Additionally, they are regulated. Failing to meet current regulatory standards can inflict stunning financial losses.

4) Weird Stuff

At a recent high school reunion, I found myself left out of the conversation because I didn’t know enough about sports or the stock market to contribute, so I blurted out “Hey! Wanna hear about weird stuff I find at trailer parks?” It worked.

The strangest stuff does in fact turn up on mobile home parks: PCB contaminated fill brought in from a pesticide factory, radioactive nuclides falling out from a burning landfill, unexploded ordinance from a former bomb factory, large containers of pure mercury, 500 cathode ray tubes stockpiled in a garage and my favorite.... graves. This is deep blue “X-Factor” stuff that you can not possibly anticipate. I am still hoping to find an alien space craft.

So how do you avoid environmental disasters when buying parks?

A Phase I Environmental Assessment performed by a qualified and experienced person is the best way to avoid environmental catastrophes, but there are also things buyers can do.

First - Ask questions of the seller, such as:

- Did you have a Phase I Environmental Assessment performed before you bought the park?

- Have there ever been any underground storage tanks on the property?

- Have there been any spills or dumping of oil on the property?

- What do you know about the earlier history of the property?

- Do you have any large quantities of paints, solvents, fuels, lubricants or other liquids stored on the property?

- What is the compliance history of your water supply and/or wastewater treatment systems?

- How old are the home heating oil tanks at the various home sites?

Secondly - Look.

Every investor walks the parks they are interested in, but they don’t always know how to spot environmental risk. When I walk a park, I spend much of my time examining the out of the way spots that are not very visible. If residents are going to dump things, they generally do it in the tree lines, ravines or anywhere that’s out of view. I have found residents avoiding trash disposal fees by tossing trash into ravines. When I walked down into one ravine, I found that it contained a significant amount of medical waste. What appears to be just household trash, can present an exceptional risk. Maintenance shops and storage sheds are a place you want to be sure to check out. It’s where you often find tanks, dumped oil, stockpiled paints and... weird stuff.

Heating oil tanks are easy to spot, but hard to evaluate. Tanks have two types of leaks: slow drips and spills that add up over time and catastrophic failures. When looking at tanks, sometimes you can smell what you cannot see. Spills and leaks may be hidden by owners who cover them up with a thin layer of soil. If you smell oil, you may have just discovered a problem. It’s hard, if not impossible to predict if and when a tank may fail. Catastrophic failures generally happen during filling and are most often the result from internal corrosion - which you cannot see. So, it’s hard to judge the likelihood of failure. However, it’s safe to say, old tanks fail more often than new tanks. Also, keep an eye out for any pipe sticking out of the ground. Sometimes home heating oil tanks are buried.

Take note of the adjoining and nearby properties. Dry cleaners, gas stations, landfills, junkyards and older factories are always of concern. New facilities tend not to have releases. It’s the older facilities where most releases to soil or groundwater take place.

Lastly - Consult appropriate professionals.

Replacing a wastewater treatment system is a huge expense. Few people can tell how much life a system has left. A civil engineer who specializes in small plants can often give you an expert opinion. If a park has a wastewater treatment plant, call a local Professional Engineer. Those with muddy boots and a bit of grey hair are generally the best. Evaluating a system takes season judgement - and judgement comes from experience.

Most importantly, retain a qualified and experienced environmental consultant to perform a Phase I Environmental Assessment. A Phase I Study has a highly standardized scope - everyone does the same things. The variable is the actual expertise and judgement of the consultant.

Choose an environmental consultant like you would choose a doctor or lawyer: you want the right professional background plus as many years of experience as possible. However, experience alone is not enough. You need an environmental consultant with the right type of expertise. The best background is hydrogeology. This is the science of groundwater. Groundwater is the primary way bad things move around underground. A hydrogeologist can judge the true likelihood of a site being contaminated. A non-hydrogeologist is more likely to recommend further study beyond a Phase I when it is not really needed. Worst of all a non-hydrogeologist may also fail to recognize issues, as they don’t understand what controls the migration of contaminants in soil or groundwater.

The bottom line is this: Just don’t look before you leap, but have a trusted expert look for what you may not be able to see yourself. The risk is great enough to warrant the effort.